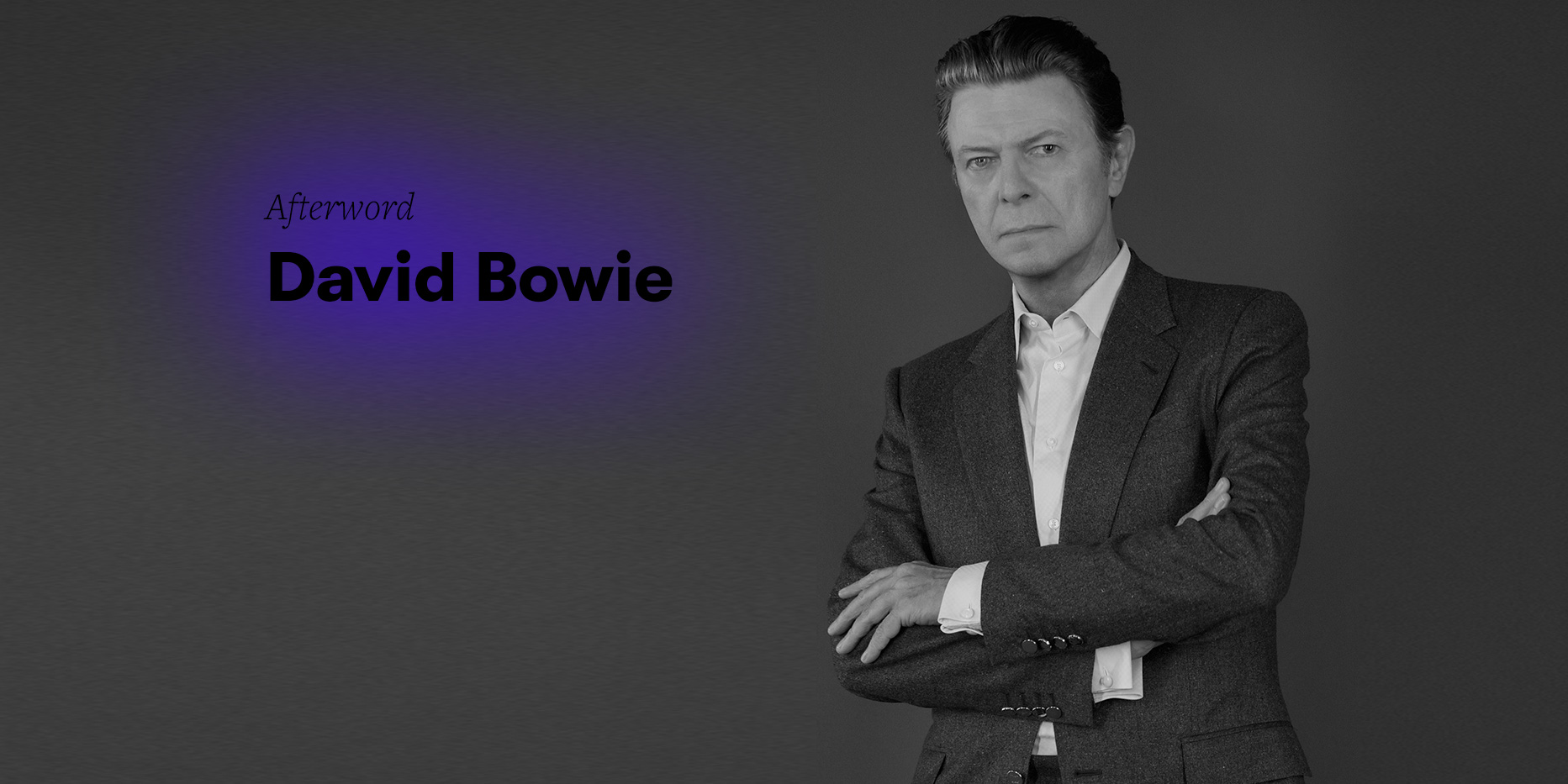

David Bowie is not simply the prettiest star—he’s a constellation. No matter which Bowie you first encountered—the orange-haired alien androgyne of Ziggy Stardust, the creepy clown in the “Ashes to Ashes” video, the louche lothario of the Let’s Dance era, or even the guy refereeing Derek Zoolander’s walk-offs—you were instantly disarmed by his style, sophistication, and presence. But Bowie was the rare rock legend whose mythology is defined more by his intellectual curiosities than his cocaine-fuelled debauchery.

The famous parade of personae that defined his astounding 1970s discography represented not just new sounds and aesthetics; Bowie was essentially a human Internet, with each album serving as a hyperlink into a vast network of underground music, avant-garde art, art-house film, and left-field literature. Bowie was the nexus through which many rock fans were first introduced to not just the Velvet Underground and the Stooges and Kraftwerk and Neu!, but also William S. Burroughs and Klaus Nomi and Nicolas Roeg and Ryuichi Sakamoto and Nina Simone. By design, most pop music is a closed loop—a rollercoaster that’s expertly designed for maximal thrills, to make you go “wheee!” over and over again. Bowie envisioned pop as Grand Central Station, the train tracks branching off into infinite new directions.

It’s hard to think of another celebrity artist who was so committed to using his elevated stature to bring transgressive ideas into the mainstream, reshaping it many times over. “Starman,” the glam anthem that made Bowie a bona fide UK sensation in the summer of ’72, wasn’t just some cosmic jive about a visiting space alien; it was the road map for a career spent luring the masses to the fringes and showing them all the weird and wonderful things happening on the other side. Even when engaging in media manipulation—like telling Melody Maker that he was gay that same year, even as his domestic life suggested otherwise—the effects were real and profound, by making the world feel a little safer for queer kids, while igniting a public conversation about gender fluidity that continues to this day. For Bowie, a vampish visage was a mere front for a deep reservoir of ideas. Even after he ditched the sci-fi costumery to focus more on musical rather than aesthetic experimentation—all while first-wave punks remodeled rock out of his discarded leather scraps and hair-dye—it still felt like he was taking us to unrecognizable places, with his late-’70s Berlin Trilogy serving as the connective tissue between the rock of the past and the electronic music of the future.

Though 1983’s mega-selling Let’s Dance proved Bowie could dominate the MTV game as well as any of the new-wave progeny he spawned, he gradually became less interested in playing it, and seemed adrift whether succumbing to glossy radio-rock or plotting reactionary retorts to it. But while his record sales may have declined considerably from the mid-’80s onward, his influence became only more firmly entrenched, as if the world was still playing catch-up with all the groundbreaking music he released in the ’70s. Through the ’90s, his presence permeated the sleazy Britpop of Suede, the industrial operas of Nine Inch Nails, Beck’s plasticine soul, and Nirvana’s mellower moods; from the 2000s on, it’s been manifest in the goon-squad disco of LCD Soundsystem, the album-to-album reinventions of Kanye West and Lady Gaga, the high-concept funk of Janelle Monae, and every time Win Butler shreds his throat trying to hit a high note to remind us we’re not alone.

The truth is, we’ve been preparing for a world without David Bowie for years. Ever since an onstage heart attack in 2004 precipitated the end of his touring career and the start of an extended hiatus from recording, listening to all the aforementioned artists over the past decade felt at times like attending a group séance, with everyone trying to tap into some elusive spectral force. And while 2013’s The Next Day was a warmly received return, its “Heroes”-desecrating cover art and death-obsessed lyric sheet made the album feel less like a triumphant comeback than an admission that Bowie was working on borrowed time.

But when Blackstar’s epic 10-minute title track was released in November, the real celebrating began: Not only was Bowie back with another new album, he sounded like he was picking up where his late-’70s experiments left off, once again pushing his music into dark, uncharted territory. And when the album was released last week, on the day he turned 69, fans celebrated a rebirth as much as a birthday.

That moment feels so very long ago. Now that we know Bowie had been fighting the cancer that ultimately claimed him, it’s impossible for Blackstar to sound like anything other than an extended death knell. Every moment on the album is now imbued with grim prophecy, from the sputtering flute that closes the title track, to the heaving breaths that open “Tis a Pity She Was a Whore,” to the increasingly disembodied quality of his voice on the fadeout of “Dollar Days,” to the omnipresent saxophone that sounds like it’s constantly beckoning him into the great beyond. And, of course, Bowie wouldn’t want it any other way. He lived his life as theater, so why would his death be any different? David Bowie’s greatest albums always opened us up to new worlds; Blackstar leads to the most mysterious, frightening, and unknowable of all.

Leave a Reply